Seneca Village Unearthed

Curator, Dr. Jessica Striebel MacLean

02.18.2020

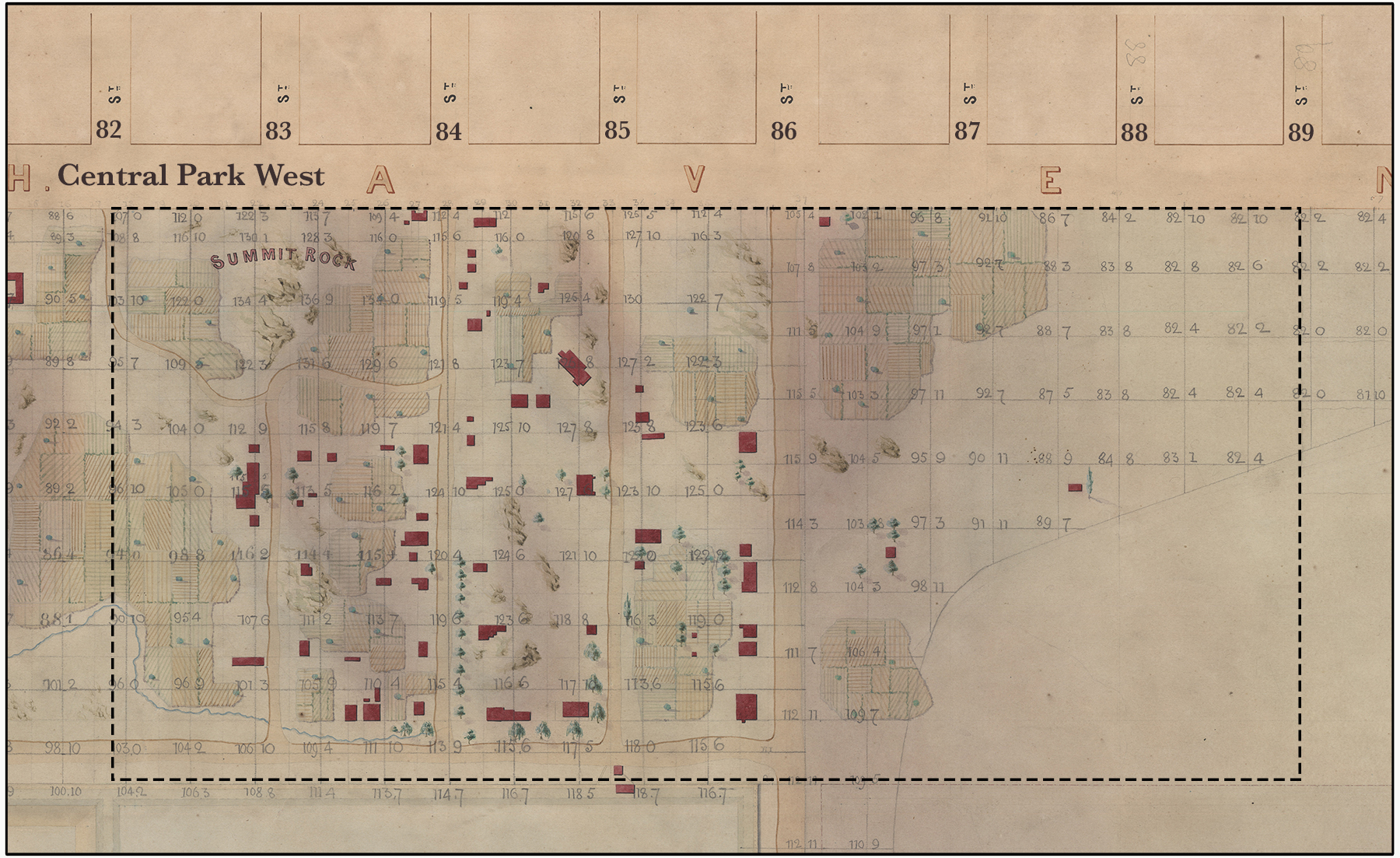

In mid-19th-century New York, Seneca Village was the largest community of free Black property owners. It was first settled in the 1820s in what was then a rural area north of the city’s center located today between 82nd and 89th Streets and 7th and 8th Avenues. Even after slavery ended in New York State in 1827, people of African ancestry continued to experience discrimination and outright oppression. The Village’s location, far removed from the city, may have brought some relief for its members from this persistent racism. By 1856 at least 220 people resided in Seneca Village. Although the community primarily consisted of Black families, it also included some Irish and German families. Historical records indicate that people of differing ancestries sometimes acted as witnesses at weddings and sponsored baptisms suggesting this was an integrated community. The village was laid out in line with the New York City grid and included three churches, a school, planting fields, and orchards, as depicted on the map below. The community was displaced in 1857 when the City of New York took the land through eminent domain to create Central Park. Seneca Village was then erased from the landscape and forgotten until recent efforts to reclaim this history.

1855 Viele Topographic Survey with the added outline of Seneca Village, courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

1855 Viele Topographic Survey with the added outline of Seneca Village, courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

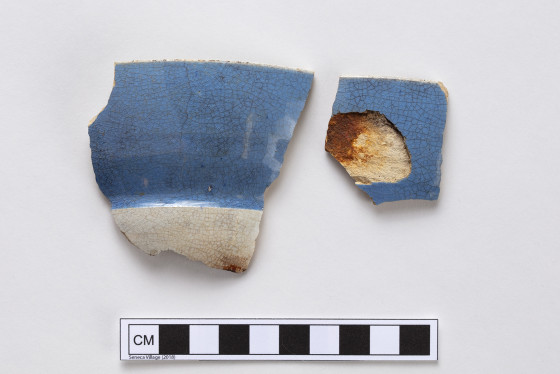

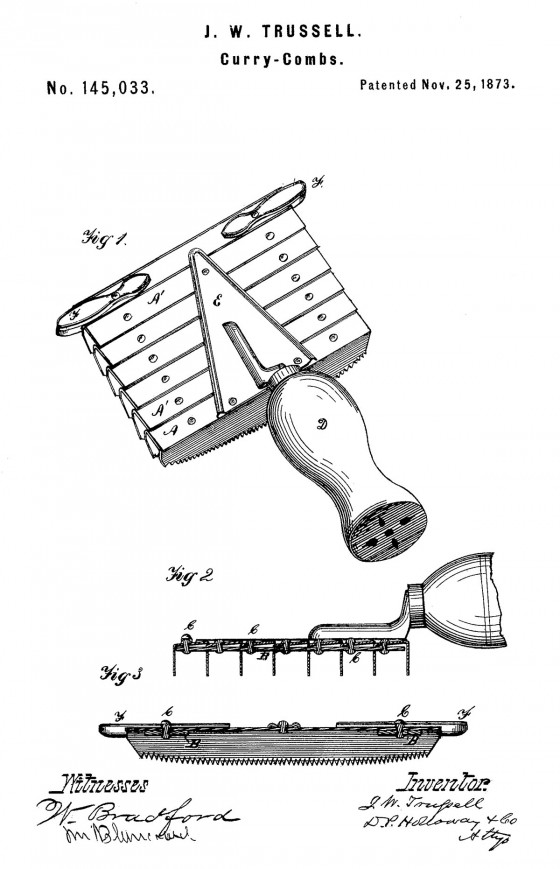

These selected artifacts are a small subset of the Seneca Village collection. They are associated with the household of the Wilsons, a Black family, which included Charlotte and William Godfrey Wilson and their eight children. Charlotte Wilson grew up in Seneca Village. Mr. Wilson worked as a laborer and was sexton of the Episcopal All Angels' Church which was located in the Village. They resided in a three-story wood-frame house with a solid stone foundation and a brick chimney. The excavations revealed that it had a tin-coated metal roof, a technology that provided greater weatherproofing and protection from fire. Archaeology also indicated that the household included many objects suggesting that the Wilsons saw themselves as members of the middle class, from the sturdy house itself to the household dishes and personal objects the family used. The recovered artifacts help us to better understand what life was like for the Wilsons and other Seneca Villagers. It was quite different from the way in which the community was depicted during the eminent domain process when their land was taken in the 1850s; at that time they were depicted as squatters (and worse), living in squalid conditions. The following overview is primarily drawn from the final archaeological report and from the writings of the excavators.

Click the hyperlink to view the entire Seneca Village Project online artifact collection.

For further information about Seneca Village:

“Discover Seneca Village” The Central Park Conservancy installed this exhibit in 2019 and leads regular tours of the historic site.

New York City and the Path to Freedom: Landmarks Associated with Abolitionist & Underground Railroad History. The Landmarks Preservation Commission released this interactive story map about the city’s abolitionist history through designated landmarks that embody it such as Seneca Village.

Wall, Diana diZerega, Nan A. Rothschild, and Meredith B. Linn. 2019. "Constructing Identity in Seneca Village" in Diane F. George and Bernice Kurchin, editors, Archaeology of Identity and Dissonance: Contexts for a Brave New World. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 157–180.

(1800 - 1857)

( - 1857)

(1783 - 1850)

( - 1857)

(1815 - 1857 )

(Early-to-mid 19th century)

(Early-to-mid 19th century)

(1843 - 1857)